Garrulax leucolophus (Hardwicke, 1815)

White-crested Laughingthrush

|

| White-crested laughingthrush in Bukit Batok Nature Park. Photograph by Choo Yan Ru |

Table of Contents

If you have been to some of the parks in Singapore, you may find this white and brown bird a familiar sight. It's commonly known as the white-crested laughingthrush, and its bold and noisy nature makes it one of the more easily noticed birds in Singapore. However, like most of the current human population, the white-crested laughingthrush is not actually native to Singapore.

Introduced or Invasive?

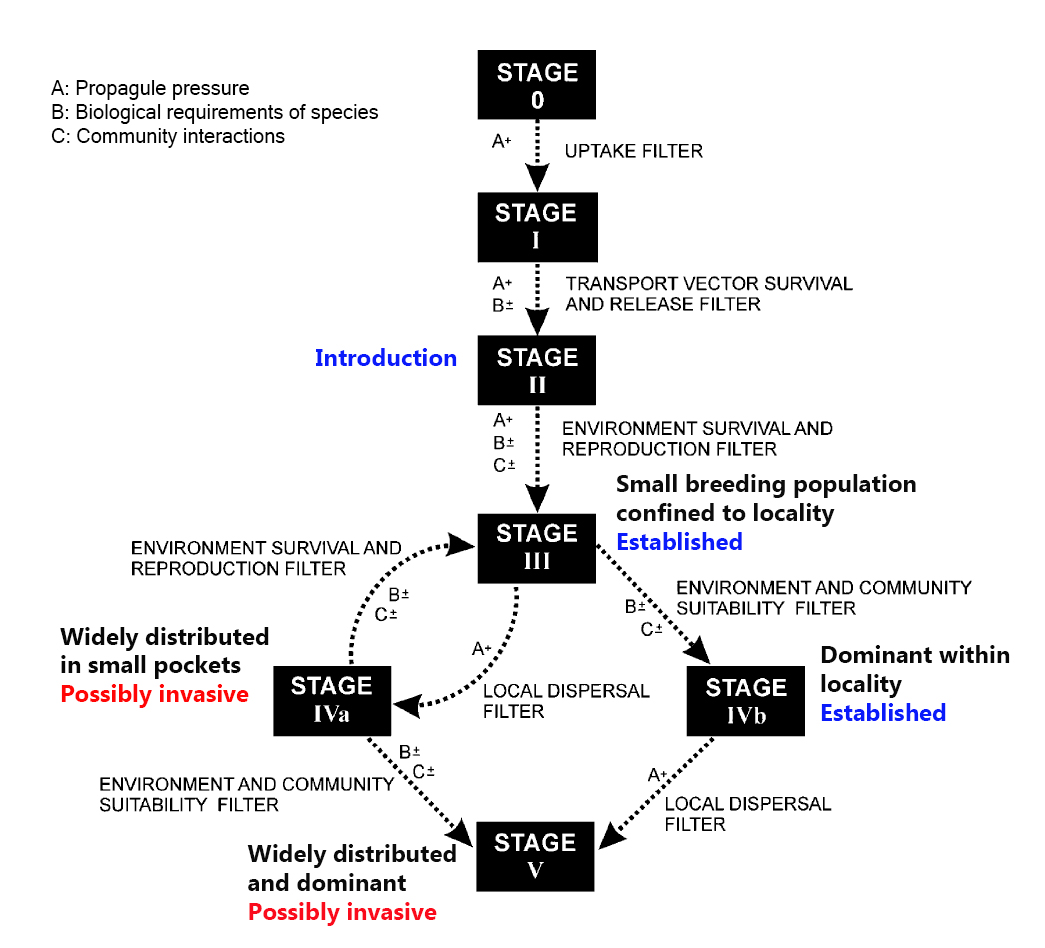

As a non-native species, the white-crested laughingthrush has been viewed with apprehension by local researchers and environmental agencies. Many local studies have considered the white-crested laughingthrush an invasive species [1][2], and it is apparently listed as such by National Parks [3]. However, while the white-crested laughingthrush is an introduced species, is it necessarily invasive? There is a tendency to conflate the two terms, even (or perhaps, especially) among biologists [4]. While the precise definitions of the terms is subjective and may vary among researchers, generally, introduced species refer to species that are found in non-native habitats due to human intervention, whereas invasive species refer to non-native species that are able to rapidly propagate beyond localised areas and in doing so, damage the local ecosystem and environment. It is important to distinguish between the two, as not all introduced species would have negative - or even significant - impacts on their new ecosystems [4]. There are several environmental barriers an introduced species has to overcome to even establish in a new environment, and most of them are unable to survive, let alone reproduce, without human intervention [5]. |

| Suggested framework to define terms used in invasion studies by Colautti & MacIsaac (2004), demonstrating the environmental barriers imposed that introduced species have to overcome before they may have a significant impact on a foreign environment. Annotations by Choo Yan Ru. (Image within Fair Use) |

However, while the exact nature of such environmental barriers may differ with location, certain traits have been observed to be common to many invasive species [6]:

- Ecological specificity: Generalists tend to be more likely to be invasive than specialist species as they are more likely to find exploitable niches in a new ecosystem [7][8].

- Native geographic range: Species with a wider geographic range may thrive in a greater range of habitats, and thus more likely to encounter suitable or familiar habitat in a new location [9].

- Reproductive success: Species with greater reproductive success may establish faster, which would allow them to propagate further and increase their likelihood of dominating an ecosystem [10].

- Migratory behaviour: Sedentary or non-migratory species are less likely to leave a new ecosystem, and may have more significant impacts on the environment [11].

- Tolerance to human presence: For an ecosystem to receive introduced species, it is likely that it has already experienced a certain degree of human-induced changes . As such, if an introduced species is able to tolerate such conditions, and to a greater extent than the local species, it may be able to out-compete local species [9].

- Taxonomic affiliation: The state of the above traits tend to be consistent within higher level taxa such as families. As such, close relatives of invasive species may be more inclined to become successful invaders as well [12][13].

These traits are thus often used as a guideline to help determine if an introduced species is likely to be invasive. How do the characteristics of the white-crested laughingthrush compare? Read the details below to find out.

Diagnostics

|

| Diagnostic characters of Garrulax leucolophus. Photographs and annotations by Choo Yan Ru. |

Size-wise, the white-crested laughingthrush averages 30 cm in length across when mature, with a tail length of 13 - 15 cm.

Distribution and habitat

|

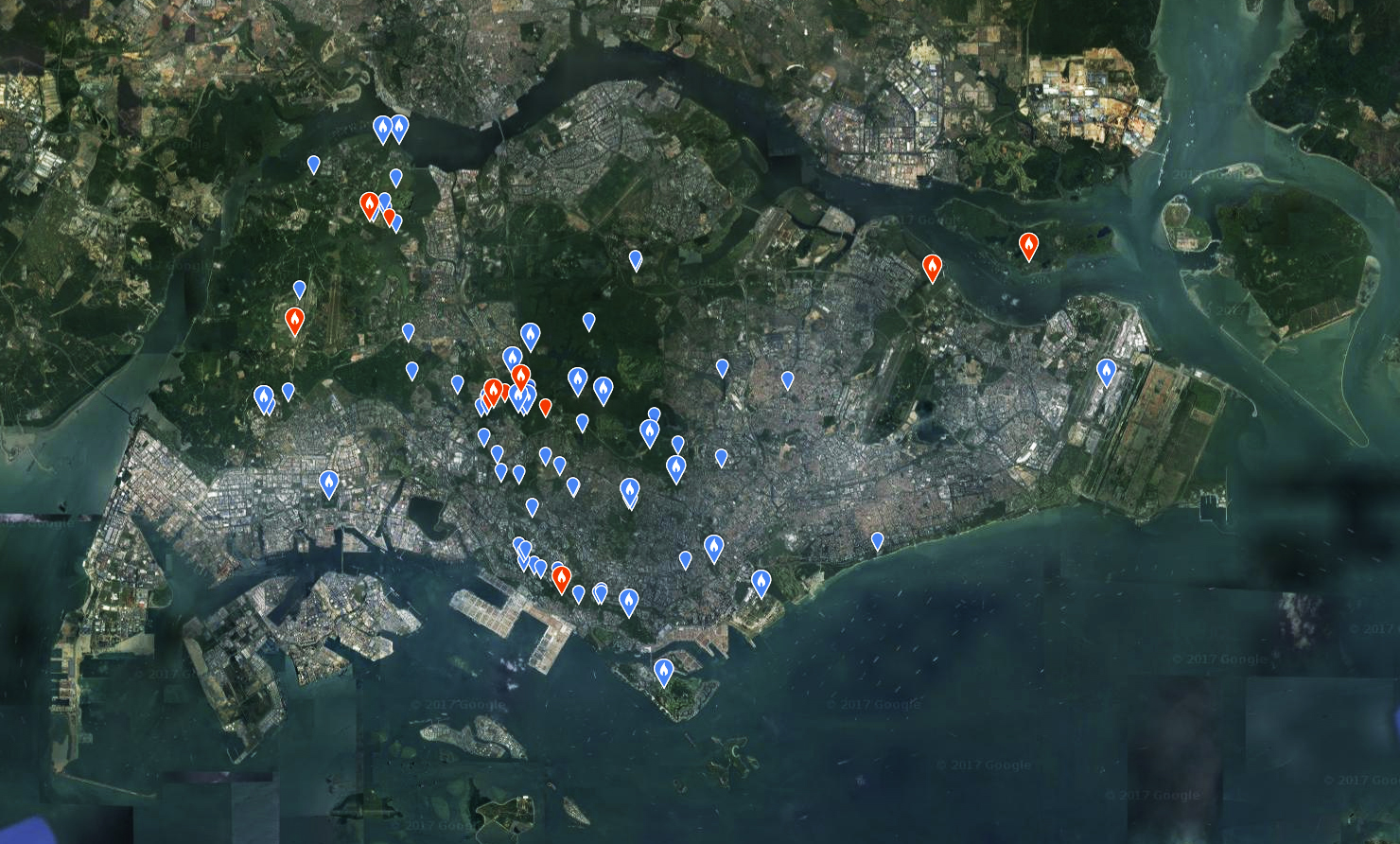

| Locations of white-crested laughingthrush sightings in Singapore[15]. Image provided by eBird (www.ebird.org) and created 15 November 2017. |

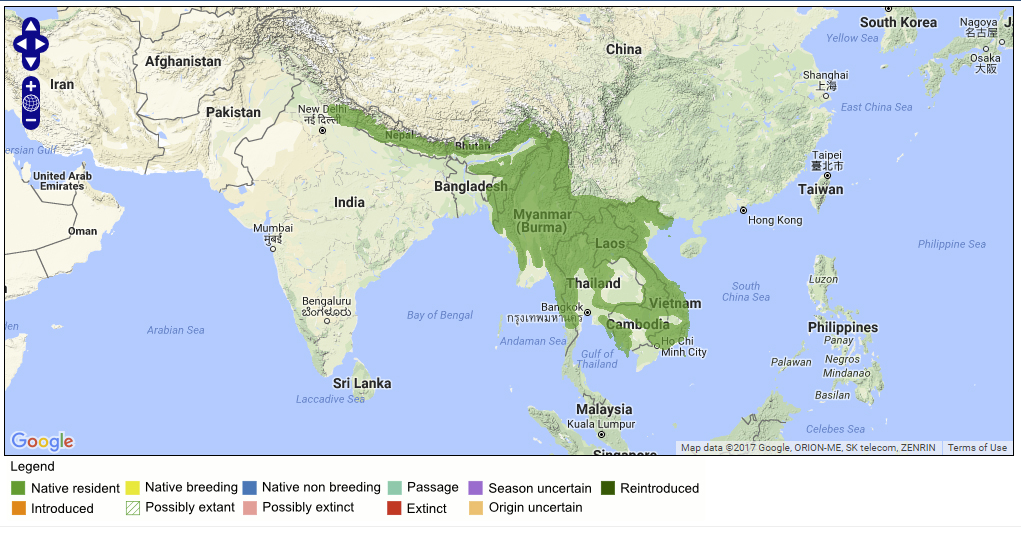

The white-crested laughingthrush is native to South Asia (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal) and other parts of tropical East Asia (Cambodia, China, Laos, Mynamar, Thailand, Vietnam) [16]. It may be found in a wide range of habitats, including broadleaved evergreen, moist and dry deciduous forest, and secondary and bamboo forests, up to elevations of 1,600 m [14]. In Singapore, it may be found in secondary and degraded forests, as well as semi-developed spaces such as parkland [17].

Biology

Social behaviour

The white-crested laughingthrush is a highly social bird, and may be found in flocks of 6-12 birds, though larger flocks have been reported. Within flocks, pairs bond by allopreening. They will also collectively defend or annex feeding grounds of both conspecifics and other bird species [1]. This social culture is an important aspect of the laughingthrush's behaviour, and heavily influences the rest of its biology.Diet

The white-crested laughingthrush forages in flocks [2]. An omnivore, it feeds on a wide range of plant and animal prey items, including fruits, nectar and invertebrates such as beetles, caterpillars and snails [1]. It is intelligent enough to deal with difficult prey, having been observed removing the hairs of a caterpillar before ingesting it (see video below). It will even opportunistically prey on small reptiles and amphibians[2].[[media type=youtube key=rVKkzrDpveA width=560 height=315 width="560" height="315"]]

In Singapore, the laughingthrush is able to feed on local fruits and small wildlife. It has also adapted relatively well to the more urbanised areas, and will forage among human waste or even solicit for food from people [1].

Growth and reproduction

Newborn laughingthrush are altricial (naked, eyes unopened, and completely dependent on their parents), but gain a full plumage in 14 days. The adults become sexually mature when they are 2 years old. They are multi-brooded, laying 2 - 6 white eggs at a time [18]. As white-crested laughingthrush flocks engage in cooperative breeding, these eggs and the hatchlings may be incubated or fed by both parents and at least one other bird in the flock, including juveniles from previous clutches [19]. Such behaviour may reduce brood mortality, and boost the laughingthrush's population density.Vocalisations

The white-crested laughingthrush is gregarious and has many distinct, structured calls of varying complexity and purposes. These calls, which are broadly categorised into calls and subsongs, have many functions. The most commonly ones are used to fight for foraging grounds, warning other members of the flock of predators, and for keeping in contact [20].| Mobbing subsong(Invading and defending foraging grounds) |

Warning call |

Contact subsong |

Recording credit: Peter Ericsson (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0) |

Recording credit: Somkiat Pakapinyo (Chai) (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0) |

Recording credit: Mike Nelson (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0) |

Is the white-crested laughingthrush an invasive species?

As an introduced species that has been established for several years and spread to many parts of Singapore, the white-crested laughingthrush has a distribution profile indicative of an invasive species. It also has many other biological qualities of an invasive species, including its generalist lifestyle, high adaptability to different environments, high birth rates and tolerance for humans. Relatively few other laughingthrush species are invasive, though the white-crested laughingthrush is closely related to the Chinese hwamei which is also introduced to Singapore and invasive in other countries [1][21][22].Local studies that generally agree that it may be a threat it to local bird species. However, while it is thought to have displaced another introduced bird, the greater necklaced laughingthrush, and is believed to be contributing to the decline of native forest babblers such as the Abbott's babbler through direct competition [1][2], none of these studies have produced conclusive evidence for such interactions. Neither does it seem to have any studied invasive impact in Peninsular Malaysia, where it has also been introduced [2]. Furthermore, the forest babblers are heavily affected by habitat degradation and fragmentation due to urban development [2], and would likely face rapid decline regardless of the white-crested laughingthrush's presence. On the other hand, the white-crested laughingthrush may be occupying ecological niches left behind by the native babblers, and may help fulfill their ecological roles in degraded habitat [2]. Considering that Singapore's habitat has undergone major transformations, with only 0.16% of primary forest cover left, and most of the remaining forest habitat consisting of young secondary forest [23], even if it is invasive, the white-crested laughingthrush may be more important than native babblers in maintaining ecosystem function. Given its ability to cross forest matrices, it may also be better at promoting gene flow between isolated forest patches through seed dispersal.

Description

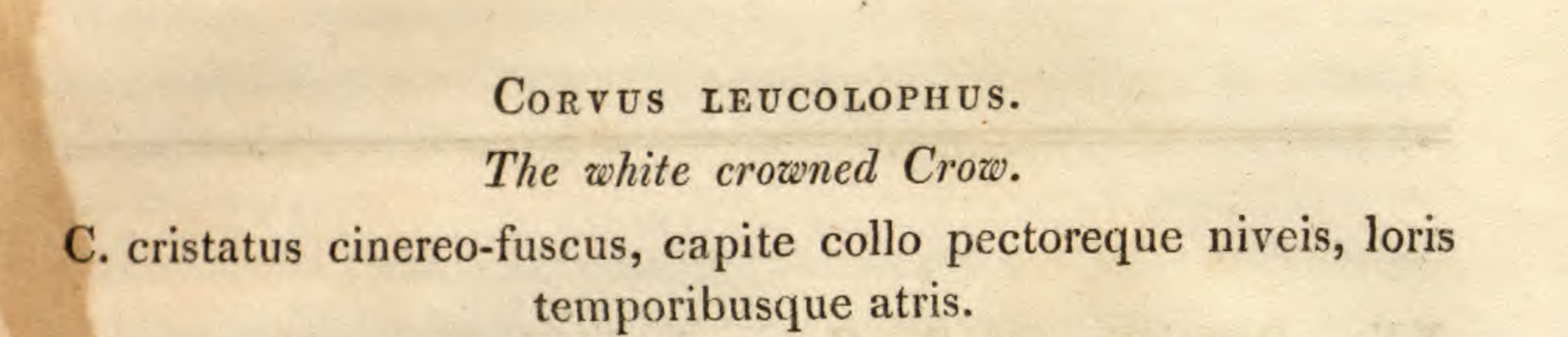

Protonym: Corvus leucolophusThomas Hardwicke, who first described the bird from specimens from India in 1815, thought it was a species of crow, and described it as such, naming it the white crowned crow.

Etymology

Garrulax is derived from the Latin word garrire, which means "to chatter".The species epithet leucolophus is derived from the Greek words λευκός (leukos = white) and λόφος (lophos = crest), and is a literal translation of its common name.

Taxonomy

| Linnean classification |

|

|---|---|

| Kingdom |

Animalia |

| Phylum |

Chordata |

| Class |

Aves |

| Order |

Passeriformes |

| Family |

Leiothrichidae |

| Genus |

Garrulax |

| Species |

G. leucolophus |

Phylogeny

i. Split from Garrulax bicolor

Garrulax leucolophus originally consisted of 5 subspecies: G. leucolophus leucolophus, G. leucolophus diardi, G. leucolophus belangeri, G. leucolophus patkaicus and G. leucolophus bicolor. However, in 2006, Collar published a study which delimited species according to a system which quantified morphological differences based on their subjective importance. The study proposed that G. leucolophus bicolor was a separate species from G. leucolophus based on differences in the following physical traits:- Blackish instead of rufous-chestnut, grey or brown body, wings and tail (major)

- More black feathers around base of bill, forming a black triangle (minor)

- More white feathers in front of the eyes, resulting in a less continuous eye mask pattern (minor)

- Black of ear coverts reduced to a thick line (minor)

- Tail 13% shorter than all other subspecies (minor)

Based on these differences, G. leucolophus bicolor was promoted to species level and renamed to Garrulax bicolor or the Sumatran laughingthrush. As a result, the white-crested laughingthrush is now found only on continental Asia, and the Sumatran laughingthrush endemic to Sumatra [24]. However, while the white-crested laughingthrush's is still classified as Least Concern by the IUCN, the Sumatran laughingthrush is considered to be Endangered [16][25].

ii. Position of clade within Aves

|

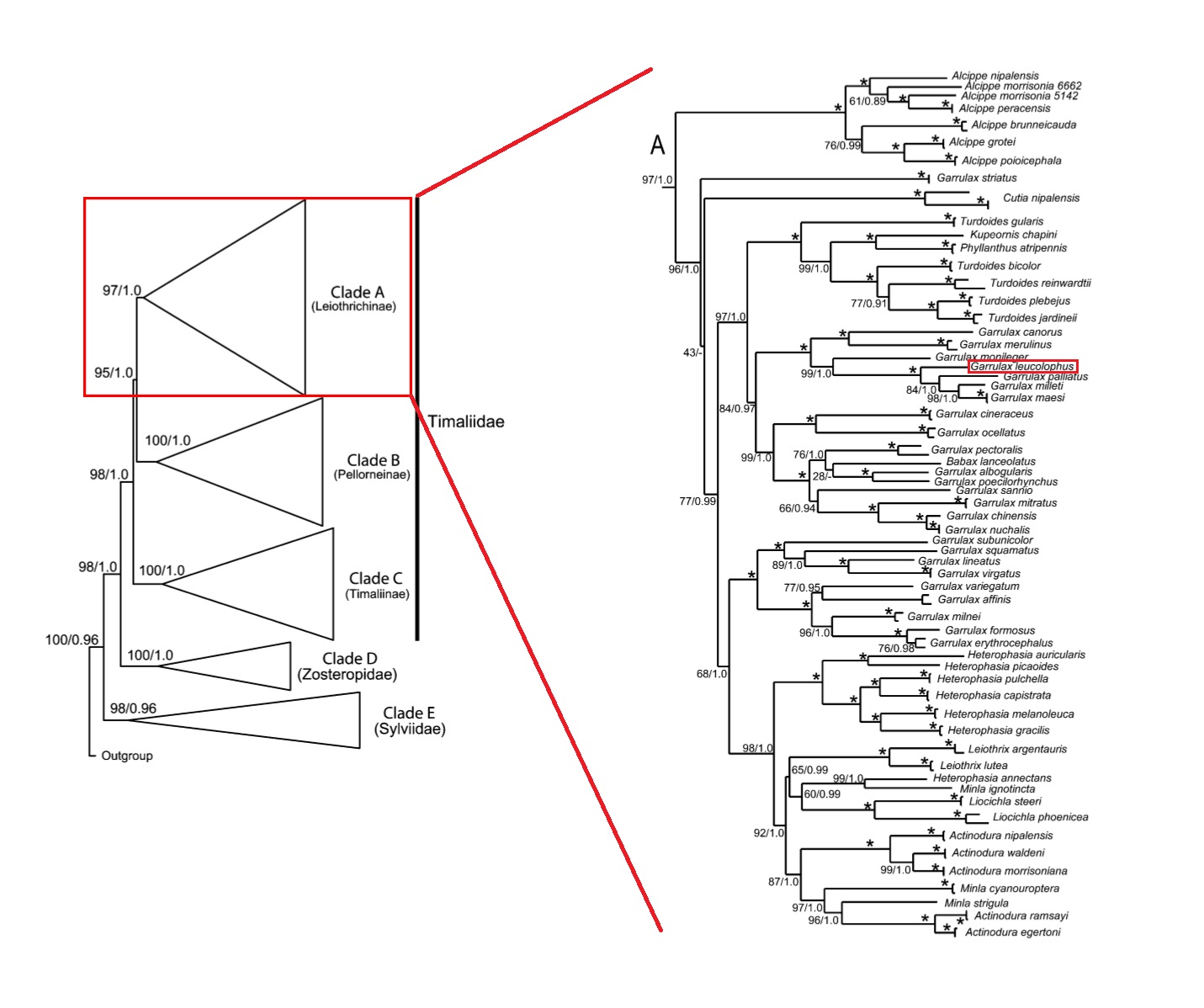

| Figures by Moyle et al. (2012) showing the three major clades within Timaliidae, and the relationships of species within Leiothrichinae (presently treated as Leiotrichidae) from ML boostrap and Bayesian analysis. The values on each node refer to (ML bootstrap support) / (Bayesian posterior probability). Asterisks indicate 100% bootstrap support and posterior probability of 1.0. Annotations by Choo Yan Ru. (Image within Fair Use) |

Garrulax leucolophus was originally placed under the family Timaliidae, a group of oscine passerines comprising of the babblers. In 2012, Moyle et al. analysed the relationships within Tiamliidae using three mitochondrial genes (Cytb, ND2 and ND3) and three nuclear introns (TGF β2, Fib5, MUSK). The sequences were aligned using MUSCLE v3.8, and phylograms were generated from maximum likelihood (ML) analysis and Bayesian inference (BI) of the characters. The resulting trees split Timaliidae into three major clades, which they proposed to be subfamilies of Timialiidae. These splits can be considered to be reliable, as they all have high bootstrap support of 95% or more, and are inferred to occur with a probability of 1.0. Timaliidae was later split into 3 families: Timaliidae, which consisted of true babblers; Pellormeidae, consisting of wren babblers and allies; and Leiothrichidae which consisted of laughingthrushes including the white-crested laughinghthrush [22].

The ML and BI trees also similar node positions below family level, and concluded that the genii Garrulax, Turdoides, Actinoduria and Minla were non-monophyletic. With regards to this, within the sub-clade that split from the Alcippe genus, there is strong bootstrap support/high probability (96/1.0) that Garrulax striatus is sister to the sampled species, and another strongly supported/highly probable (97/1.0) node that broadly splits the rest of the Garrulax genus between two clades. This subsequent split indicates that some of the Garrulax species, including Garrulax leucolophus, may share a common ancestor with the Turdoides species, Kupeornis chapini and Phyllanthus atripennis, while other members of the Garrulax genus may be more closely related to the genii Heterophasia, Actinoduria and Minla.

However, the position of the latter Garrulax assemblage may not have been reliably placed as the node that splits it from Heterophasia, Actinoduria and Minla has poor bootstrap support on the ML tree despite a high probability of occurrence on the BI tree (68/1.0). This low bootstrap support indicates that the node is not consistently reproduced when the parameters of the ML tree are resampled, resulting in high variance around the estimated node, indicating that the model parameters available were insufficient to accurately resolve the node's position. In contrast, the high Bayesian posterior probability of the node indicates that the split has a high probability of occurring given the provided parameters, but by itself does not indicate if there were errors introduced by the model parameters or if the model was sufficient. As there was no further statistical evaluation of the Markov-Chain Monte Carlo calculations, it could not be determined if the posterior probability was a indicator of tree topology accuracy than the bootstrap support values. Given that relatively few character states were used in this study, it is more likely that there were insufficient parameters, and that the posterior probability may change with more data.

References

[1] Yap CAM & Sodhi NS (2004) Southeast Asian invasive birds: ecology, impact and management. Ornithological Science 3(1):57-67.[2] Wong SHF (2014) The spread and relative abundance of the non-native White-crested Laughingthrush Garrulax leucolophus and Lineated Barbet Megalaima lineata in Singapore. Forktail 30:90-95.

[3] Low BW (2015) Non-native Wildlife in Singapore. mygreenspace 4(27)

[4] Davis MA, et al. (2011) Don't judge species on their origins. Nature 474:153.

[5] Colautti RI & MacIsaac HJ (2004) A neutral terminology to define 'invasive' species. Diversity and Distributions 10: 35-141.

[6] Blackburn TM & Duncan RP (2001) Establishment patterns of exotic birds are constrained by non-random patterns in introduction. Journal of Biogeography 28(7):927-939.

[7] Brooks T (2001) Are Unsuccessful Avian Invaders Rarer in Their Native Range Than Successful Invaders? Biotic Homogenization, eds Lockwood JL & McKinney ML (Springer US, Boston, MA), pp 125-155.

[8] McLain DK, Moulton MP, & Sanderson JG (1999) Sexual selection and extinction: The fate of plumage-dimorphic and plumage-monomorphic birds introduced onto islands. Evol. Ecol. Res. 1(5):549-565.

[9] Blackburn TM & Duncan RP (2001) Determinants of establishment success in introduced birds. Nature 414:195.

[10] Richard P. Duncan, Tim M. Blackburn, & Sol D (2003) The Ecology of Bird Introductions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 34(1):71-98.

[11] Sol D & Lefebvre L (2000) Behavioural flexibility predicts invasion success in birds introduced to New Zealand. Oikos 90(3):599-605.

[12] Lockwood JL (1999) Using Taxonomy to Predict Success among Introduced Avifauna: Relative Importance of Transport and Establishment. Conservation Biology 13(3):560-567.

[13] Blackburn TM & Duncan RP (2001) Establishment patterns of exotic birds are constrained by non-random patterns in introduction. Journal of Biogeography 28(7):927-939.

[14] BirdLife International (2017) Species factsheet: Garrulax leucolophus. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 15/11/2017.

[15] eBird (2017) eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance maps. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed: 15 November 2017)

[16] BirdLife International (2016) Garrulax leucolophus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22734757A95096142. Downloaded on 15 November 2017.

[17] Wang LK & Hails CJ (2007) An annotated checklist of birds of Singapore. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, Supplement 15:1–179.

[18] Coles D (2007) Management of Laughingthrushes in Captivity, 44 pp.

[19] Round P (2006) Cooperative provisioning of nestlings in the White-crested Laughingthrush Garrulax leucolophus. Forktail. 22:138-139.

[20] Chinkangsadarn S (2012). Singing behavior of White-crested Laughingthrush (Garrulax leucolophus). Science 19:55-60

[21] Dai CY & Zhang CL (2017) The local bird trade and its conservation impacts in the city of Guiyang, Southwest China. Regional Environmental Change 17(6):1763-1773.

[22] Moyle RG, Andersen MJ, Oliveros CH, Steinheimer FD, & Reddy S (2012) Phylogeny and Biogeography of the Core Babblers (Aves: Timaliidae). Systematic Biology 61(4):631-651.

[23] Yee ATK, Corlett RT, L SC, & Tan HTW (2011) The vegetation of Singapore - an updated map. Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 63(1 & 2):205-212.

[24] Collar NJ (2006) A partial revision of the Asian babblers (Timaliidae). Forktail 22:85-112.

[25] BirdLife International (2016) Garrulax bicolor. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22734448A95085919. Downloaded on 01 December 2017.